BEYOND THE FARTHEST...SNOWBALL?

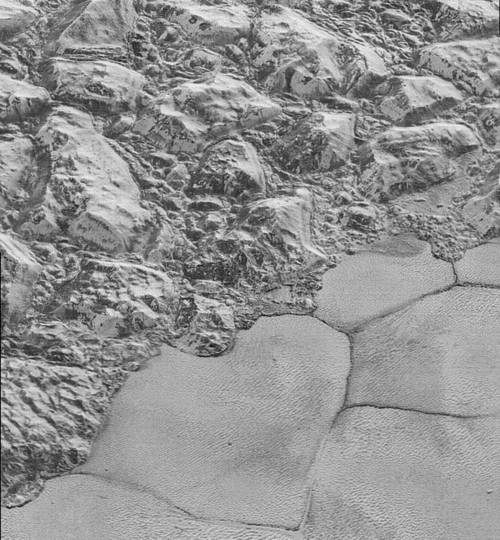

/Image courtesy of NASA/JPL

Congratulations to the China National Space Administration for the successful landing of their Chang’e-4 spacecraft on the far side of the Moon January 3rd (the first time it’s ever been done), as well as the deployment of the Yutu-2 rover. Its tracks in moondust prove China is now a major player in space exploration.

Other than that, recent space news stories are full of exotic names and exotic places—names like the Kuiper Belt, Oort Cloud, Ultima Thule, Farout (which sounds more like the expression of an enthusiastic hippy than a scientific designation!)

In the first minutes of New Years Day 2019 the NASA spacecraft New Horizons hurtled past an object identified as (486958) 2014 MU69, a name that doesn’t fall trippingly from the tongue so it was given a nickname chosen by the public: Ultima Thule, an ancient Greek and Roman phrase meaning the farthest of places, beyond the known world. It isn’t actually even the farthest place in our solar system, but it is now the most distant object ever visited by a man-made device. New Horizons is the craft that sent terrific pictures back from Jupiter and then went on to astonish us with stunning images of Pluto, so it’s a little probe with a great track record. Since Ultima Thule is more than 6.4 billion kilometres from Earth, receiving data from New Horizons is a slow process (it will take many months for all of it to come in), but pictures show what’s called a “contact binary”, meaning two objects that formed separately but then fused together into one, and it looks like a reddish snowman about 30 kilometres long. The scientific community has long expected that the so-called Kuiper Belt beyond Neptune consists mostly of objects like slush balls made of water, ammonia, and methane that orbit the Sun as far away as fifty AU (astronomical units—the distance between the Sun and Earth). Learning more about Ultima Thule will increase our knowledge of how the solar system was formed.

The other trans-Neptunian object to get attention recently is one nicknamed Farout, officially 2018 VG18. Discovered in November 2018, Farout is the most distant object ever observed in our solar system. It’s currently between 125AU to 130AU from the sun—about 3.5 times as far as Pluto—though its orbit will carry it farther and closer to the sun at times. As unimaginably distant as that is, our solar system is thought to extend much farther to include the theoretical Oort Cloud, a spherical area that might extend as far as 200,000 AU from the sun and be composed of more slushy iceballs, remnants of the original cloud from which the solar system formed billions of years ago. The Oort Cloud hasn’t been observed directly, but is thought to be the source of many comets with very long orbits. By comparison, the nearest star to ours, Proxima Centauri, is currently about 268,500 AU away (4.246 light years).

Such distances are incredible when considered in a straight line, but to recognize that they apply in every direction, in three dimensions, the sheer volume of space involved is truly beyond our minds’ ability to process. After all, you could fit all of the planets in the solar system side by side in just the space between the Earth and our Moon with room to spare, so a sphere 100 AU across and more is one heck of a lot of real estate!

What could be “out there”? That’s the domain where theoretical astronomy and science fiction thinking converge. A fertile realm for the imagination.

Could there be a super-Neptune “Planet X”, ten times as big as Earth? Or the proposed brown dwarf star ominously named “Nemesis”? If so, why not a whole second planetary system orbiting in the darkness?

Could there be life? We already know of microbes and other life forms that can survive under the most extreme conditions. We have no reason to assume that life couldn’t arise in those dark realms. Even on Earth some forms of life in the deep oceans depend on chemical energy rather than the sun. At the very least, if all those slush balls and hypothetical dark planets don’t support native life, they could still provide waystations (or hiding places) for visitors from other stars. Are there advanced aliens watching us from the shadowy borders of our home system? Fleets of conquering ships just waiting for the order to strike? Maybe one navy with plans to conquer, battling with another determined to save us from enslavement. (Maybe I’ve been reading too many space operas!) Or what if there are giant life forms, planet-sized or larger, to whom we’re no more significant than bacteria?

If comets can be knocked out of the Oort Cloud by a galactic tide and fall toward the Sun and inner planets, could there be larger, much more dangerous threats lurking beyond sight? Vagabond moon-sized rocks? Maybe wandering black holes remorselessly devouring everything in their paths? (Actually, scientists would probably have spotted such powerful gravitational effects. Phew!)

Flights of fantasy aside, I’m kind of partial to the idea of giant forms of life “out there”. SF writer Robert J. Sawyer described mega-beings made of dark matter in his novel Starplex. It just feels right that such vast spaces should be inhabited by something and not simply empty voids. I also think it’s quite possible that alien visitors would bide their time in the dark reaches, observing us before deciding to make contact.

Some people may wonder why we go to such effort and cost to send a machine six billion kilometres to look at an oversized slushball. The fact is, in investigating things we expect to find in the great beyond, we really have no idea what we might find. That’s what makes it so exciting.