HOW MANY WORLDS DO WE NEED?

/A few months ago UK astronomers published some findings that might be evidence of universes parallel to our own. You can read an overview here. It raises a subject much beloved by both physicists and science fiction writers.

Maybe I should have asked, “How many worlds do we need to explain the state of the universe?” Maybe more than we could ever count.

Quantum theory is the science of trying to understand the behaviour of the very smallest particles and energies that make up everything we see and touch. At that level, things get really weird—often contrary to what we’d expect from our observation of the larger world around us. One of the key tenets of quantum theory (according to the widely held Copenhagen interpretation) is that particles exist in a state of probability. For example, an individual electron is located within a kind of cloud of possible locations until we somehow observe it or interact with it. It exists in a state known as the quantum waveform until the act of observing it causes the waveform to collapse and reveal a precise location. To make things more confusing, that observed location of the electron is only relative to the observer, not necessarily to the wider universe. If you’re thinking that this makes the universe feel incredibly imprecise, I can’t disagree. Not only that, but the implication of the theory is that the existence of everything depends on there being an observer (kind of the ultimate expression of the age-old dilemma: “if a tree falls in the forest with no one around to hear it, does it make a sound?”) So who is this observer? Us? God? An alien on planet Zyglug?

There are other problems with the interpretation too (look up “Schrodinger’s Cat” if you’re not already familiar with it) so in 1952 David Bohm proposed an explanation called decoherence which suggested that the waveforms don’t actually collapse, but the information (ie. the location of the electron) leaks into the world outside the wave and can be observed. Then in 1957 Hugh Everett theorized that, in essence, the electron exists in every possible location in a multitude of separate universes which never interact with each other—no waveform collapse required (but an infinity of different dimensions!) This came to be known as the many worlds interpretation.

On the scale of our everyday human life, science fiction writers took this to mean that whenever we face a choice (even as small as deciding to turn left or right at an intersection) we actually do both, creating two new universes that then proceed along new, separate paths. See why I used the word infinite? Because this doesn’t just apply to every human being and every possible decision we make, but to every single particle in the universe and every possible motion each particle could take.

Naturally, science fiction took to this idea like a cat to cream, and hundreds of stories have since been written involving alternate realities, alternate histories etc. with interesting variations. I recently enjoyed how a novel called Time Machines Repaired While U Wait by K.A. Bedford combined the many worlds concept with time travel. In Bedford’s future world, time machines are a consumer item, and you can go back in time to change some things (maybe to reverse a terrible decision that ruined your life) but while you might go on to enjoy a new and improved timeline, the old one still exists with the original version of you still schlepping through the same bad life. Not a perfect solution!

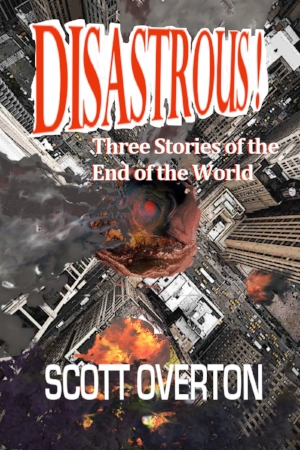

I’ve always objected to the many worlds interpretation just because it’s so unwieldy—a whole separate universe for every possible motion of every single particle in the cosmos? Seriously? But my scepticism hasn’t prevent me from occasionally riffing on the idea myself in my fiction. Have a look at a story of mine called “No Walls” in which the protagonist tunes himself in and out of other dimensions in order to pass through solid objects like a ghost (and runs afoul of some major pitfalls).

The many worlds interpretation provides writers with a truly endless list of potential plots and settings, but it also forces me into an interesting conclusion:

If the multiverse theory is true, then everything that’s possible (including what’s possible in alternate universes where even the laws of physics are different) actually exists. In that case, there is no such thing as science fiction and fantasy, because even the most complex futuristic societies and the most exotic fantasy realms are reality…somewhere.

No more arguments over whether Star Wars is SF or F—it’s just mainstream fiction set a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away (in another dimension!)